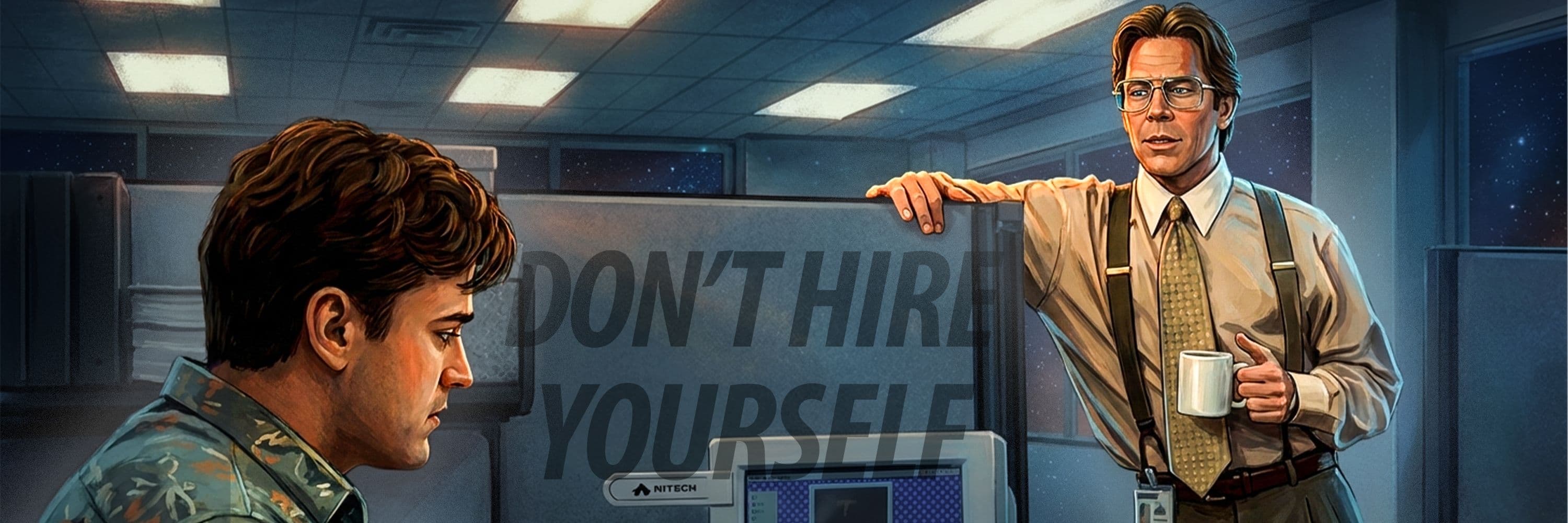

Founders love the feeling of recognition.

You meet someone early, maybe as a cofounder candidate, maybe as your first “serious” hire, and the conversation feels unusually smooth. They speak your language. They mirror your ambition. They validate your instinct. They don’t make you explain yourself.

It feels like relief.

For first-time founders especially, that relief can be the trap.

Because hiring your lookalike often looks like “alignment,” but it behaves like something else over time: ego-matching, impatience with craft, and a quiet rivalry for authorship. The company becomes a stage for identity, not a system for results.

The Comfort of the Lookalike

The lookalike hire makes you feel understood.

They agree quickly. They talk in big frames. They can sound “visionary” on demand. And because they resemble your own temperament, you mistake familiarity for fit.

It’s the same bias that shapes friendships and social circles. People cluster around the familiar. The difference is, in business, familiarity can be expensive.

The job of early hiring is not to find someone who “gets you.” It’s to find someone who builds what you cannot build, sees what you cannot see, and holds the line when your personality starts distorting the company.

Teams don’t become strong by echo. They become strong by balance, productive disagreement, and clear roles. Even research and practitioner guidance around cofounders emphasizes diversifying skills and responsibilities instead of duplicating them.

What Lookalikes Cost Over Time

The first cost is instability.

A certain kind of lookalike, especially the highly ambitious one with low patience for daily work, tends to treat your company as a temporary chapter. They jump from place to place because they believe the problem is always the environment, never their own consistency.

They’re “too big” for the role. Too smart for the pace. Too talented for the constraints. Until reality catches up, and it always does.

The second cost is internal damage.

These profiles often weaponize competence. They talk down to others. They treat teammates as tools. They interpret feedback as disrespect. They use the company to prove themselves rather than build the company.

If they leave, it becomes dramatic. If they stay, it becomes political.

And if they’re a cofounder, the risk is sharper: the lookalike doesn’t just want to contribute, they want to replace. The logic becomes, “If I’m like you, then why aren’t I you?” That’s where “partnership” quietly shifts into contest.

Capability Isn’t the Risk, Ego Without Craft Is

None of this is a warning against strong people.

Founders should hire capable people. That’s one of the few real advantages you can create early, and it compounds. But there’s a difference between capability and identity-driven ambition.

Capability shows up in behavior: finishing, improving, testing, shipping, owning outcomes.

Identity-ambition shows up in language: big promises, constant repositioning, obsession with status, and a strange allergy to the boring work that actually makes companies win.

The risk is not intelligence. The risk is a person whose self-image is bigger than their tolerance for repetition.

A good founder doesn’t fear talent. A good founder fears the personality that needs the company to worship them.

Complement, Don’t Clone

The best early teams don’t look like mirrors.

They look like puzzles that lock together.

One person carries vision and judgment. Another carries operational rigor. Another carries product taste. Another carries revenue discipline. The exact combination changes by business, but the principle stays the same: you’re building a system, not a fan club.

Even Google’s work on team effectiveness points toward factors like psychological safety and team dynamics over “stacking similar stars.” Great teams aren’t great because everyone thinks the same, they’re great because the environment allows truth, challenge, and reliability.

If you hire your own personality repeatedly, you don’t get a team. You get multiplied bias.

The Profile That Builds With You

The person you want is usually less theatrical.

They don’t need to sound impressive. They don’t need to announce their ambitions every day. They’re willing to carry the weight of small execution without needing to label it “revolutionary.”

They can disagree with you without disrespect.

They can be loyal to the mission without being loyal to your ego.

They can take feedback without turning it into a war.

They can work inside constraints without complaining that constraints exist.

Most importantly, they’re not trying to use your company to prove they’re exceptional. They’re trying to build something exceptional.

That’s a huge difference.

A Simple Filter Before You Hire

Before you hire someone early, ask a question that sounds personal but is actually structural:

Are they here to build, or are they here to become?

Builders get quieter over time and stronger in results.

Status-seekers get louder over time and lighter in output.

If the person’s primary energy is identity, you will pay for it later in culture, trust, and focus.

The market doesn’t care how ambitious your hire sounded in week one. It only cares what the company can repeatedly deliver.

Closing: Don’t Hire a Reflection, Hire a Counterweight

Hiring your lookalike feels efficient because it reduces friction early.

But companies don’t fail because the early months were uncomfortable. They fail because the foundation was built on personality instead of performance, on agreement instead of truth, on ambition instead of craft.

Hire brilliant people, yes.

Just don’t hire the version of brilliance that can’t be coached, can’t be grounded, and can’t respect the boring work that makes winning inevitable.

If you hire yourself, you don’t get a team.

You get an echo. And echoes don’t build companies.